Gallery

Photos from events, contest for the best costume, videos from master classes.

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|

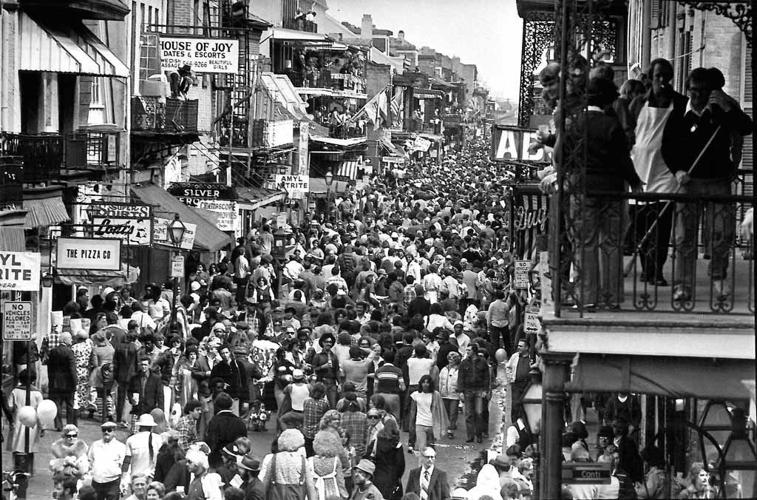

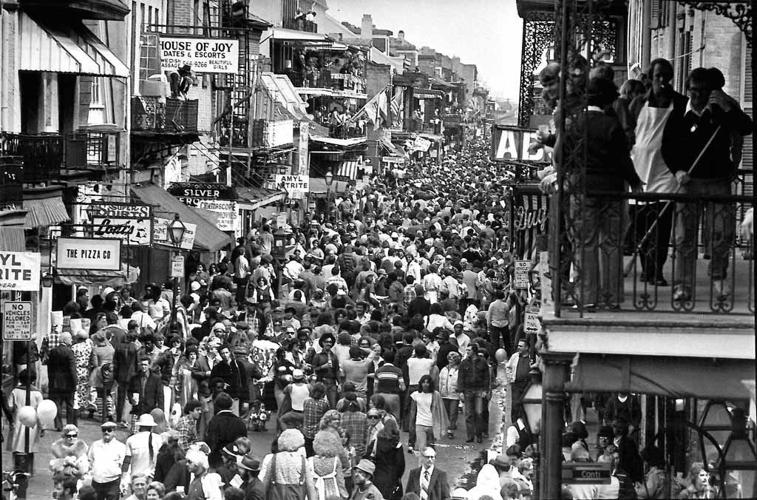

Defiant New Orleans police officers burn uniform shirts on the steps of police headquarters at 715 S. Broad St. on Feb. 9, 1979, the second day of a strike that threatened Mardi Gras season parades. In 1979 the New Orleans police department went on strike, using the powerful leverage of Mardi Gras to push for an improvement in their working conditions. The city held fast and the celebration was cancelled. Ish. Some parades moved just out of town. Most tourists stayed away, fearful of unregulated reveling. Photo by Robbie McClaran. M ardi Gras has been an intrinsic element of the rhythm of life in New Orleans since the city’s founding. In 1699, when French Canadian explorer Jean Baptiste Le Moyne de Sieur Bienville arrived on the banks of the Mississippi River some 60 miles below the crescent of land where he would establish la Nouvelle-Orleans, he christened the site Pointe du Mardi Gras. in The decision 40 years ago by New Orleans Police officers to strike was historic by any means, but even more so since it came just three weeks before Mardi Gras - in February 1979. However, many members of different krewes did end up getting together to throw a ball on Lundi Gras and to do one patriotic-themed parade on Mardi Gras Day as the Krewe of Patria. Before the recent COVID-19 cancellation, the last time parades didn't roll in New Orleans was in 1979 because of a conflict between the New Orleans Police Department The cancellation of Mardi Gras would give New Orleans “a worldwide black eye,” a group of concerned citizens said in a full‐page newspaper advertisement last Friday, the day the police Though 1979's parades didn't roll, Mardi Gras celebrations continued in the French Quarter, with members of the National Guard patrolling the streets. As The New York Times put it: "Cancel Mardi Gras? The 1979 police strike may have rearranged Mardi Gras, but it certainly didn’t cancel it. Even in paradeless Orleans Parish, the party continued in the streets, in homes and at private balls. New Orleans' police officers went out on strike twice in February 1979. The first walkout was designed to gain recognition of the union, bring the city to the bargaining table, and force agreement on selected economic demands. It lasted 30 hours and was successful. Still, in all, the spirit was more than preserved, and as Mardi Gras 1979 ended, the city was true to a philosophy of Fat Tuesday: “When you're dead, you're dead. Long live the living!” The Gay Solidarity Group organised the 1979 and 1980 Mardi Gras Parades. Ken Davis gives the background for the second parade. Barry Power was roped in by his work mate, Lance Gowland to help in 1979 and in 1980. The after party was a novel add on for the parade in 1980 and Philip King describes how it happened. In Then and There, I document a crucial aspect of public behavior at the 1979 New Orleans Mardi Gras.Shooting with an instant SX-70 Polaroid camera, the process allowed me to directly interact with my subjects who perform, observe, and even share in the photographic process. Mardi Gras (UK: / ˌ m ɑːr d i ˈ ɡ r ɑː /, US: / ˈ m ɑːr d i ɡ r ɑː /; [1] [2] also known as Shrove Tuesday) is the final day of Carnival (also known as Shrovetide or Fastelavn); it thus falls on the day before the beginning of Lent on Ash Wednesday. [3] In 1979, twenty four years old and fresh out of art school, I moved to New Orleans with little more than a backpack and a camera bag. Within a few days I found a slave quarters apartment in the French Quarter and began spending most waking hours photographing on the streets. <br /> By a quirk of history, that same year the New Orleans Police Department staged a strike during Mardi Gras and February 19, 1979. By Max Mickel. Way down yonder, New Orleans Mayor Ernest Morial was predicting that "it might take us more than a decade to recover" from the Mardi Gras that, more or less, wasn Fee and Art’s features a solo exhibition of vintage Mardi Gras images by Portland-based photographer Robbie McClaran.. STATEMENT In 1979, twenty four years old and fresh out of art school, I moved to New Orleans with little more than a backpack and a camera bag. "We wanted the folks doing the negotiating to know they couldn't hold Mardi Gras hostage," said Brooke Duncan, a former Rex and the organization's captain in 1979. By 1981, Mardi Gras had switched from winter woollies in June to bare flesh in February and had replaced protest songs with disco beats. In the process, an enduring dilemma for the parade’s In 1979, twenty four years old and fresh out of art school, I moved to New Orleans with little more than a backpack and a camera bag. Within a few days I found a slave quarters apartment in the French Quarter and began spending most waking hours photographing on the streets. By a quirk of history, that same year the New Orleans Police Department staged a strike during Mardi Gras and most of Dureau created this poster for the Mardi Gras season of 1979. George Valentine Dureau was born December 28, 1930 and died April 7, 2014. Dureau was an American artist whose long career was most notable for charcoal sketches and black and white photography of poor white and Black athletes, little people, and amputees.

Articles and news, personal stories, interviews with experts.

Photos from events, contest for the best costume, videos from master classes.

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|